Hypoplastic left heart is one of the most severe heart defects with cyanosis and is also known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

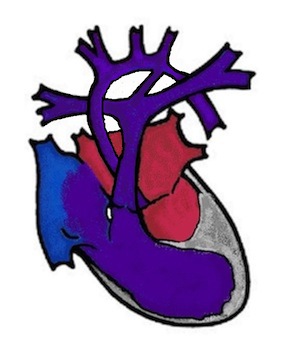

This is the underdevelopment of the entire left side of the heart. This includes the mitral valve (heart valve between the left atrium and left ventricle), the left ventricle (left main chamber), the aortic valve (heart valve of the main artery) and the aorta (main artery) with the aortic arch. The heart valves can be narrowed (stenotic) or completely closed (atretic). As the left side of the heart is not functioning, the baby is dependent solely on the right side of the heart for blood flow to the body and lungs.

What are the effects of hypoplastic left heart syndrome?

In the womb, the child is doing well and usually grows normally. After birth, the connections between the right and left heart, which are present in every baby, close. These are the foramen ovale (hole between the right and left atrium) and the ductus arteriosus (vessel between the pulmonary artery and the aorta). This occurs in the first hours of life up to around the third day of life. In hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the blood accumulates in the left atrium because it can no longer drain into the right atrium via the foramen ovale. In this heart defect, the right ventricle not only pumps its blood into the lungs, but also into the systemic circulation via the ductus arteriosus. If the ductus arteriosus closes, which occurs in every newborn, the circulatory system receives hardly any blood and the baby suffers a circulatory shock. Unrecognised, the child dies within a short time. The infusion of the drug prostaglandin to reopen the ductus arteriosus is then life-saving.

Symptoms

Every child with HLHS is cyanotic (blue) or very pale, and breathing is usually laboured. During the examination, a very fast heartbeat (tachycardia) and very weak pulses are noticeable.

How is hypoplastic left heart syndrome treated?

A child with HLHS has the best prospects if the diagnosis is known before birth. The delivery is then planned in a centre that has experience in caring for these children.

Medication

After the birth, the medication prostaglandin is started immediately as a continuous infusion. This usually succeeds in reopening the ductus arteriosus within a few hours and stabilising the circulation.

Nach der Geburt wird sofort mit dem Medikament Prostaglandin als Dauerinfusion begonnen. Damit gelingt es meist innerhalb weniger Stunden den Ductus arteriosus wieder zu öffnen und den Kreislauf zu stabilisieren.

Catheter intervention

A cardiac catheter intervention can be performed to widen the foramen ovale. This involves inserting a catheter into the umbilical vein or a vein in the groin up to the heart and directing it from the right to the left ventricle. There, a balloon that sits on the catheter is inflated, thus widening the hole in the dividing wall between the ventricles. This procedure is also known as the Rashkind procedure.

Operation

Unfortunately, there is no way to stimulate the left side of the heart to grow in HLHS, so the only option for these children, apart from a heart transplant, is to have the right side of the heart do all the work in the long term using a three-stage surgical procedure. The operations are very complex and you can read the details under the heading Sugical techniques. The most important steps are listed here

1. The Norwood operation (or a variant of this, the Sano operation)

The outlet from the right main chamber is created by connecting the pulmonary artery with the small aorta, the small aortic arch is widened, the dividing wall between the ventricles is removed and finally blood is channelled to the lungs via an aortopulmonary shunt. This operation is performed in the first 10 days of life and is technically the most difficult step in the operation for the surgeon.

2. Glenn anastomosis

At the age of 4-6 months, the large vein in the upper half of the body (vena cava) is sutured to the right pulmonary artery. This operation is a good relief of the right main ventricle and the children usually thrive very well afterwards. In the best case, oxygen saturation is around 85%, which means that the child remains slightly cyanotic but is doing very well.

3. Total cavopulmonary anastomosis (TCPC)

The third operation is performed at around 3 years of age (2-4 years). The large vein in the lower half of the body is also connected to the pulmonary artery. There are various techniques for this, the most commonly used today is total cavopulmonary anastomosis (TCPC), in which a tube (tunnel) is passed around the outside of the heart and connects the vein to the pulmonary artery. This type of venous blood supply to the lungs was first invented by the Frenchman "Francis Fontan" in the 1980s and the circulation achieved with it is also known as the Fontan circulation.

Hybrid procedure

Since the end of the 1990s, another treatment option has been developed in which the goal is also a Fontan circulation, but in which the first step of the treatment is stent implantation in the ductus arteriosus and a restriction of the pulmonary circulation with a surgically applied pulmonary artery banding of the right and left pulmonary artery. With this technique, parts of the Norwood operation and the Glenn operation can then be performed in a single operation, which is carried out around the 4th month of life. The Fontan circuit is then completed in exactly the same way as described above. This procedure also requires a great deal of experience, not only of the surgeon but also of the paediatric cardiologist.

Living with hypoplastic left heart syndrome

To support the heart, some children require long-term medication and the blood is thinned with Marcoumar (anticoagulant) or aspirin (platelet inhibitor) to prevent blood clots from forming. Children with HLHS are no longer cyanotic (blue) after the third operation and, although they are missing one half of their heart, they are surprisingly resilient. Nevertheless, it must be taken into account that the heart of a child with HLHS ages more quickly. Therefore, all large centres that care for such patients have developed follow-up programmes to detect and treat deterioration at an early stage. This is primarily done with medication, but some patients may also require a heart transplant.